I had the best manager ever at SAIC. Her name was Janie Harris.

She had little technical background and didn’t want any more. But she was the department head over three divisions worth of more than 400 scientists, engineers, and lawyers (odd collection) at the apex of her department.

Janie didn’t want to impress you with her problem-solving skills. She didn’t want to tell you how to do your job. She didn’t even understand your technical problems. But she was always available to talk.

She may not have known the technologies of her department, or the complexities of our data, or even what, exactly, we did for a living. But she knew this: if we were having fun, we were doing good work. If we were not having fun, our work suffered. So she would ask us, in her own way, “are you doing good work?”

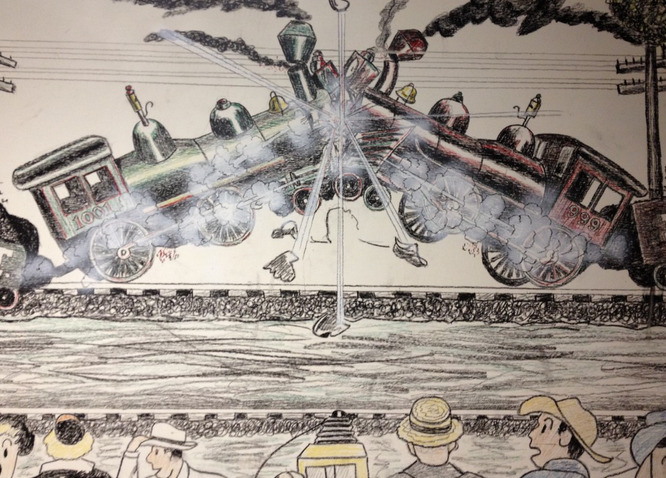

Her office was huge. Along one wall hung maybe three dozen funny hats. She would don those during her department tours. The tables that ran the perimeter of two walls had toys of all manner and make: from Mexican yo-yos to wind-up choo-choos to flying contraptions. People speak openly when their hands are busy.

Every time I entered her office with something on my chest, I’d pick up a toy and I’d fidget with it while we chatted.

How’s your fun per unit time?

Janie loved to tour the floor, coming into each office (everyone had their own, private office in Janie’s department) and ask the most technical question she ever knew, “How’s your fun per unit time.”

She may not have known the technologies of her department, or the complexities of our data, or even what, exactly, we did for a living. But she knew this: if we were having fun, we were doing good work. If we were not having fun, our work suffered. So she would ask us, in her own way, “are you doing good work?”

If we said we were happier than a woodpecker in a puppet factory, she’d chat with us for a few more minutes, give us a toy she’d brought from her office, and move on to the next office.

If we said we were having no fun, she’s delve. “Who is making your life hard?” she’d ask.

It’s never a “what”

She knew it was never a “what,” but a “who.” And we learned to tell her outright. Sometimes, though, Janie would act as a sounding board until we figured out the “who.”

Sometimes it was one of her division managers. (That was the case for one division more than another; mine.) But usually, it was another peer or even the client.

When that happened, Janie was on the phone gathering the friction-producing members together in a meeting room. This didn’t happen in hours. It happened in minutes.

It always followed the same script: “Jeff has a problem. You are jeff’s problem. Why are you jeff’s problem?” That kind of approach was blunt, to the point, and in time, we learned that it was not an accusatory but a factual statement.

She knew it was never a “what,” but a “who.” And we learned to tell her outright. Sometimes, though, Janie would act as a sounding board until we figured out the “who.”

No politics. No egos. No pussyfooting.

Let’s solve the problem.

The problem often turned into two… or three… and before you could say “gitcherbuttinhere” we had all parties to the friction in one place. And we talked through the friction.

I never saw a problem persist past an hour in her department. And her department grew from 52 (when I started) to over 400 (when I left).

After the meetings, we’d all leave feeling like we’d gotten something done, and energized to go out and do more good work.

Janie’s reign didn’t last. None do. Her success brought her down.

Her fellow department heads got jealous of Janie’s “most profitable,” “highest net,” “smoothest run” department in the building and they began to conspire to take it all away from her.

Eventually, they did. She told us this was coming and told us not to worry. She’d be okay (and she was).

(That’s another tale of preparedness for another time.)

The department collapsed to a small number of most-political climbers and the gilded age was over.

Good managers don’t survive in corporate surroundings. But they sometimes show up and then flash like shooting stars.

Thank you, Janie. You were bright, if brief.